Through me one goes into the town of woe, Through me one goes into eternal pain, Through me among the people that are lost. …………………………………………………………… ALL HOPE ABANDON, YE THAT ENTER HERE! –Dante Alighieri, “Inferno” Canto III, Langdon Trans.

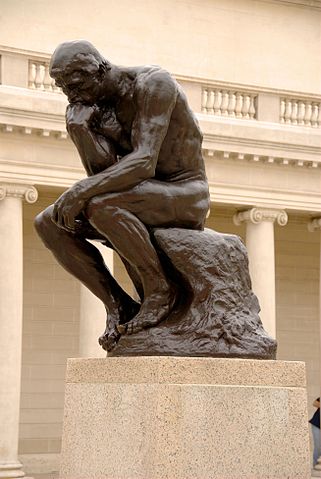

To me, maintaining his famous pose throughout history, “The Thinker” lives on as one of the most inspirational works of art the world has ever seen. Just looking at him makes me want to sit down and come up with great thoughts. Or as Winnie the Pooh so wisely says, “Think, Think, Think.” However, I had never really examined this great work’s history until recently, when I learned The Thinker is only a small part of a far greater and even more amazing sculpture.

A controversial artist, Auguste Rodin live in late 19th century France. Highly influenced by the works of Michelangelo and fascinated with sculpting and stonework, Rodin completed several exquisite works (1). Many of these remain popular today, including “Eve” which actually sold for $18,969,000 at a Christie’s Auction in 2008 (2). What a woman! Nonetheless, his most famous work is probably that know as “The Gates of Hell.”

A true piece of beauty, “The Gates of Hell“ took 37 years to create and involved 200+ carefully depicted and constantly adjusted human sculptures covering the gate doors. Along with works like “The Three Shades” and “The Kiss,” “The Thinker” originally formed only one of the many sculptures lining “The Gates of Hell“; only afterwards was it recast and enlarged as a separate piece. The scene was initially inspired by Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, one of three parts to the Divine Comedy, a famous tale of Dante’s walk through Hell, Purgatory, and up to Heaven (3).

“The Gates of Hell” originally sought to portray Dante as The Thinker looking down upon the peoples described in The Inferno’s depiction of Hell, but over time Rodin began to broaden the meaning of the work. Ultimately he noted that:

The Thinker has a story. . . Guided by my first inspiration I conceived another thinker, a naked man, seated upon a rock, his feet drawn under him, his fist against his teeth, he dreams. The fertile thought slowly elaborates itself within his brain. He is no longer dreamer, he is creator (4).

The other figures on the gate continue to depict images of “universal human emotions and experiences, such as forbidden love, punishment, and suffering, but they also suggest unapologetic sexuality, maternal love, and contemplation” (3). The writhing bodies of the men, women, and children consumed by agony and passionate expressions of emotion are truly a moving sight.

If you look carefully, you can still see some figures from Dante’s work. For example, one figure is that of “Ugolino and His Sons.” They appear in Canto 33 of the Divine Comedy; Ugolino was a tyrant accused of corruption who fled with his two sons. The sons starved to death, and dying slowly of hunger, Ugolino committed the great sin of eating their dead bodies. This was recently proven to be just a legend (5) , but in Dante’s work, Ugolino is confined to the worst level of hell for his crimes.

Rodin’s work is amazingly precise in its design; the figures seem so human that the draw the viewer in. I wish my mind worked this way; such amazing artistry never ceases to amaze me!

Lovely piece on Rodin. Thanks. And since you’re at the University of Iowa School of Law, you might also want to look into Rodin’s “The Burghers of Calais”. A figure from that larger piece (“Jean de Fiennes”) stands in the courtyard of the Boyd Law Building. Iowa’s “Jean de Fiennes” is the twelfth and final cast made from Rodin’s model (unless France changes its policies about casting). Iowa’s “Jean de Fiennes” is displayed as Rodin wanted, almost at ground level. Calais on the other hand ignored him and set their Burghers on a tall pedestal with a wrought-iron black fence around it. Awful, as photos of that siting show. Rodin wanted the townspeople to be able to wander around the figures at street level in the town square, an emblematic joining of past and present Calais. After World War II, Calais changed the siting, but it still isn’t right. If Rodin could have cast the piece directly on the cobblestones, he would have. One city has set its Burghers on cobblestones, but I can’t find the photo or the city at the moment.

The closer a viewer gets to “Jean de Fiennes” the more astounding it becomes. The young face is open, dismayed, questioning. The arms are outstretched, palms up, and in company of the other figures, it’s clear that Jean has turned to look back at Calais. His thin garment is long but doesn’t cover his bare feet. Haunting.